Zahutu’s Leaflets: Concerning the Three Incarnations [1]

By Dr. Chester I. Zinchief

Of three incarnations of the artist I will tell you; how the artist becomes a little girl; or a penguin; or a snowman.

There is much that impedes the artist, the patient servant who would produce any desired thing: but the greatest and most persistent barrier is that which the artist must assail.

What is this impediment? asks the artist that would be known, and listens dumbly like a little girl, awaiting instruction. What is this great impediment, O masters, asks the artist that would do anything, that I may learn its ways and strength? Is it humbling oneself to the virtues of the past? Letting their wisdom shine through to mock my own?

Or could it be: jumping onto the largest ship, even if it is overcrowded? Taking long journeys to consult with the ancient kings, even when they are grown mute?

Or could it be: eating the oatmeal and smeat of beauty and, for the sake of popularity, suffering boredom in one’s mind?

Or could it be: feeling ill and asking strangers to comfort you, and making friends with the deaf, who speak and never listen?

Or could it be: plunging into freezing oceans when they are the oceans of beauty, and not avoiding jellyfish and crabs?

Or could it be: worshipping those that despise us and resurrecting the ghosts that have left us?

All these barriers the artist that would become popular must take upon herself: like the little girl that, instructed from overpowering masters, learns without effort, and acts without question, and eschews the tempting void of the Poles.

On the barren iceflows of the Arctic, the second incarnation appears. Here, the artist becomes a penguin, isolated from the concerns of the world and master of his domain. He hunts in isolation, he evades his final enemy: he wants to escape him and the words of god; for immortality he must avoid battle with the Irate Iguana.

What is this giant lizard whom the artist will not obey? “Thou shalt, Pokey! Now!” is the name of the giant lizard. But the penguin-artist says, “No, green-eyed dragon, I will!” Irate Iguana stands in his way, distracting as a stoplight, surrounded by his motorcycle cavalcade; and on every biker’s shoulder is a tattoo that says, “Thou shalt, Pokey! Now!”

Aesthetics, centuries and centuries old, are discussed by the bikers in this cavalcade; and the mightiest of lizards speaks thusly: “All beauty is owned by me. All beauty has long been discovered, and I am all discovered beauty. Truly, I say unto you, there can be no more ‘No, green-eyed dragon, I will!’” This says Irate Iguana.

Dear friends, what good is the artist who is a penguin? Why should the little girl, who is obedient and imitative, not suffice?

To find new beauty--the penguin will not often do; but the discovery of artistic freedom for new creation--that is the chief goal of the penguin. The example of liberty and the damned refusal of all convention--these are the products of the penguin. To evade the past and shirk its boundaries--that is an impossible goal for the little girl that would remain loved. Truly, to her it is destructive, and better left to solitary creatures. The little girl must worship “Thou shalt, Pokey! Now!”; the penguin must dismiss these orders through deliberate ignorance, and seek only his own path, that freedom from beauty may become his goal: the penguin is needed for such triumph.

Now look look now, friends, what can the snowman do that the penguin can not? Why must we seek out the living simulacrum and leave behind the penguin? The snowman is experience and erudition, a new conclusion, a game, a mocking and parasitic machine, a moved mover, a blessed “Maybe.” For the creation of art, my friends, a blessed “Maybe” is necessary: the artist now chooses his own rules, unearths the riches of the penguin, and reinvents the world.

I have now told you about three incarnations: how the artist becomes a little girl, or a penguin, or a snowman.

This said Zahutu. Then he set off again, to the band that is called the Motley Crew, to find his long-lost parka.

Reflections

A fair complaint levied against Pokey the Penguin is that the reader receives far too little indication of the author’s ability and intent. There are hundreds of web comics superficially similar to Pokey, and one cannot be reasonably expected to investigate them all in good faith. The vast majority of sloppily drawn, cut-and-paste comics are random, unamusing, and shallow. Even if we allow that Pokey the Penguin is an exceptional comic, the amount of inspection required to see the smallest fraction of Pokey’s aesthetic value would tend to deter serious critics.

The traditional conception of artistry is not a sudden “incarnation,” but a gradual evolution. Artists are expected to study the works of past masters (phase 1), gradually increase their own abilities according to traditional standards, and, if particularly masterful, come to reject old standards (phase 2) or create new ones (phase 3). In our current world, where art has no defined boundaries, this traditional evolution helps to protect the artistic world from talentless shams; a proven artist can experiment in abstract forms, but one with no clear talent will not easily find recognition (in theory, anyway). Steve Havelka clearly belongs in the category of unproven artists, and thus encounters difficulty in presenting his work.

Zahutu’s leaflet of the three incarnations contradicts the principle of artistic evolution, naming instead three different categories of artists that do not evolve into further forms, or each other. The Little Girl serves only the desires of others, shaping her art according to current standards of beauty and current topics of interest. She studies successful artists of the past and follows their principles; she will do whatever is required to become popular and loved. Zahutu uses the word “beauty” here as a powerful restriction upon art; “beauty” being a highly variable and subjective term, those who seek to create beauty only serve popular sentiment and ancient prejudice.

The Penguin is an artist working in ignorance of all rules and conventions, seeking only to entertain and educate himself; he must constantly avoid knowledge of aesthetics and artistic theories. The Irate Iguana represents the body of aesthetic theory that, upon discovery, will spoil the pure creations of an ignorant artist. The Penguin is not necessarily superior to the Little Girl, and his output is not generally of any particular worth, but his creations will serve as an example for the Snowman.

The Snowman is the supreme artist, familiar with other artists and theories, but following or skirting custom as he sees fit. Unlike the Little Girl, the Snowman can create new forms of art and beauty; unlike the Penguin, the Snowman can build upon the accumulated knowledge of past artists. The Snowman must have the ability to discern which customs are of use to him, and which are not; he must have the ability to not only break with tradition, but to create as if he had never known it. The Snowman is not a simple evolution from either of the lower forms, and he gains knowledge from the experiments of both.

The most significant claim of Zahutu’s leaflet is that an artist’s work can actually suffer from over-exposure to aesthetic theories. Once one has knowledge of how things “should” be done, it becomes difficult to otherwise, except in a self-conscious and inhibited way. For example, Beethoven may be thought of as the archtypal “evolved artist,” beginning with quite normal compositional styles and later deviating more and more from traditional forms. However, even at his most unique, Beethoven sounds more like Mozart than a jazz quartet. There is no reason why Beethoven couldn’t have moved toward jazz-like music (although many would argue it’s a damn good thing he didn’t), but neither he nor any other traditionally schooled composer created anything even vaguely resembling jazz. Jazz (and later rock and roll, and later rock’n’roll, and later rap) came from uneducated people making music however it pleased them (of course, well-educated composers later moved into popular styles). If all musical artists had been instructed in classical composition, popular music would be quite different today, if indeed any kind of massively popular music would exist at all.

However, jazz and rock’n’roll are not better than classical music. While the Penguin is singing Yesterday and the Little Girl is playing Moonlight Sonata, the Snowman is listening to both and taking in what he desires. We may argue about who are the Penguins and Snowmen and Little Girls in the musical world, but that is of no great concern here. In the world of comic art, Steve Havelka is an archetypal Snowman. His comics are a mixture of playful experimentation and deliberate creation that would not come from an experienced cartoonist.

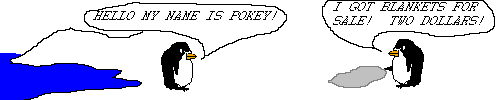

The two panels above are the beginning and ending of comic # 20 (Blankets For Sale). Although the intervening panels distract from the “punchline,” the funny part of the comic is that Havelka’s rendering of a blanket is an amorphous blob that could equally well represent a plethora of other items. The Comic does not develop with any intentional movement toward the ending joke; rather, Havelka discovers the ambiguity of his drawing and decides, on the spot, to make a joke out of it. This joke requires the ability to step back and see the comic as others would, to think about the multiplicity of images, and to alter a premise in mid-comic. It also requires that the artist draw very poorly. Havelka’s comics often rely on a balance of amateurish goofiness and highly refined observations.

[Editor’s note: The next seventy examples have been omitted.]