Pokesthetics [1]

by Alfred Dutsch Agosto

It’s like ten thousand spoons/

When all you need is a knife.

--Alanis Morrisette in Ironic

When I first heard this insipid line, it had a startling effect on me. It was the late nineties, I think, and a friend of mine, Josh Harper, had decided to extol the simple virtues of Alanis Morrisette’s apathetic anthem of dull observations. My brother and I grew indignant at Harper’s foolish worship, and we disputed that there was anything ironic about having spoons when you need a knife. The argument soon denigrated into sarcastic bickering, and as I brandished a gigantic dictionary with a triumphant air about me, a dark shadow fell over us. After a few minutes of squinted reading and semantic discussion, we still could not agree what irony was, but we had all agreed that the dictionary was wrong.

In my sophomore year of high school, an English teacher told my class that irony was an unexpected occurrence. We all knew, from common usage, that irony signified more than surprising events, but because we could not put our thoughts into words, we coalesced, and squeezed our conception of irony into the bland package we were given. Sarcasm, for instance, is a division of irony: saying the opposite of what you intend to imply is unexpected, and thus ironic. Finding one thousand spoons before a single knife is improbable, and therefore unexpected, and therefore ironic.

My debate with Harper incited the rebellion I had hitherto avoided through lazy obedience to a lazy instructor. But it wasn’t my teacher’s fault. Irony is improperly defined in every dictionary I have ever seen. Everyone knows what irony means, and most people use the word “ironic” on a quasi-daily basis, but no one has effectively put into words what “irony” signifies. In my searches, I have found three basic definitions repeated over and over. Simplified, the definitions amount to these:

A) Irony: surprising occurrence.

B) Irony: sarcasm.

C) Irony: surprising occurrence that seems to mock expected occurrence.

Definition C comes closest to accurately describing irony, but as we will see, C only captures a smaller subset of irony. For the moment, let us focus on the broader definition of A.

Consider the three following situations, and, using your inherent understanding of irony, decide which one seems most ironic to you:

1) The given name of a librarian is Booker Bookman.

2) The given name of a librarian is Xxx Yyy.

3) The given name of a librarian is Zim-Zam O’Pootertoot.

Of the three, #1 is the least unexpected (or “most expectable”), in that “Booker” and “Bookman” are both existing names. #2 is probably the most unexpected, as the name is unfamiliar, unpronounceable, and unlike all usual names. The third situation is slightly less surprising, in that “Zim-Zam” and “O’Pootertoot” at least mimic the basic structure and appearance of real names (If either of those are real names, I apologize. I have never seen them, and invented them trying to create nonsense words.) According to the dictionarial definition of irony, #2 is the most ironic, #3 the second most ironic, and #1 the least ironic.

However, I doubt that you reach the same conclusion when using common sense (I certainly do not). #2 and #3 are debatable, but #1 is clearly the most ironic. Our task is to discover why.

Obviously, the answer lies in the connection between the word “book” and the profession of a librarian. In actuality, when we hear the name “Booker Bookman,” we do picture someone whose life is associated with books. Of course, Booker did not choose his name, and there’s no reason to believe that his family had any recent professional connection with books, but it is virtually impossible for an English-speaker to hear the name “Booker Bookman” and not think of a man associated with books. It is this expected association, and not simple unexpectation, that creates the irony.

In a broad sense, we might say that it is unexpected for someone’s name to relate to his or her profession, and that Booker Bookman’s existence is ironic for that reason. In part, this is true, because people do not usually have names that relate to their professions. However, it is even more unlikely that anyone would be named “Xxx Yyy” than that a librarian would be named “Booker Bookman.” The unlikelihood of an event is only part of its irony, and being unexpected is not enough to warrant the designation of irony. Irony involves a variation on expected connections or logical outcomes, but greater variation does not imply greater irony.

The key to Booker Bookman is that his profession seems to follow logically from his name (or vice versa), but it does not. Our instantaneous reactions to the name “Booker Bookman” tell us the man is involved with books; we note he is a librarian and our instinctual assumptions are satisfied; but on further contemplation, we realize that Bookman’s name and profession are related only by coincidence (barring the psychological influences of being named “Booker Bookman”). Booker Bookman tempts us toward a logical connection, while simultaneously denying that such a connection exists. We can also see that the irony of Booker Bookman does not come by mocking an expectation, but by fulfilling an irrational one.

Ironical Halos

Grading levels of irony becomes difficult when we realize that irony is a balance between rational and irrational connections. If something is completely reasonable and expected, then it is not ironic; yet, if it is completely random and unpredictable, it is still not ironic. As irony involves an interplay of opposing forces, it seems that irony is forced to exist in a certain bounded region, between sense and nonsense, in which we cannot determine which way is up.

Irony can be compounded, of course. For instance, there might be a homosexual librarian named Gaylord Bookman. This situation is more ironic than #1, even though it involves the same basic expectation manipulation, because the ironic content is more-or-less doubled. By slipping more ironies into the situation, I have increased irony without addressing the rationality/irrationality ratio [2] . In other words, I have cheated.

It is tempting to make simple conclusions about the R/I ratio. We could say that the R/I ratio should approach 1 as irony increases, as any rationality in excess of irrationality (or vice versa) would be superfluous. We could hypothesize a perfect R/I ratio and test our conclusions against self-reports of quantified irony in various situations. We could say that rationality and irrationality cannot be quantified, and that a numerical ratio is impossible.

I am rather skeptical that any numerical representation of the R/I ratio is at this time possible. The most important concept for us right now is that irony involves an interplay between rational and irrational connections. This interplay gives birth to the model I have created and named “the ironic halo.”

The simple diagram above involves a variable situation A. The point in the center represents a totally rational connection between events; one event implies the other, without any possible exception. For example: Some X are Y; some Y are X. As you move further away from the central point, the connections become unnecessary or only slightly implied; e.g. that person’s name is Jane; that person is a woman. Outside the gray halo, there is no rational connection between events; there is not even any guarantee that common subject exists in the separate events; e.g. My wife has died; Napoleon slept six hours every night.

The gray area forms a boundary between connections that are excessively rational and connections that are excessively irrational. The gray “ironical halo” represents those events that have an appropriate R/I ratio, and are thus ironic.

Pokey the Penguin and the R/I Ratio

Whether or not my understanding of irony has captured all usages of the word “irony,” it describes well enough the humor of Pokey the Penguin that we can begin to understand how the comic is constructed. Many readers mistake Pokey as a senseless comic because they ignore the rational connections and focus on the irrational ones; to do so is to miss the point entirely. In virtually every Pokey comic, the humor is centered on a balanced R/I ratio.

Before I begin a short analysis of each Pokey the Penguin comic, I wish to restate the fact that the R/I ratio is a helpful concept, and not a mathematical value. There is no need to measure rationality or irrationality in these comics, but one must keep in mind that both factors are present.

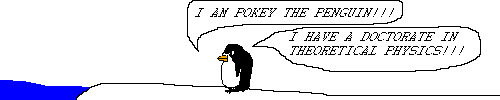

#1 Pokey the Penguin

The first Pokey comic is straightforwardly ironic. It claims to be an educational children’s cartoon, but is full of errors and contains the slightly offensive portrayal of Italians as evil thieves (the Italians will later become Pokey’s arch-enemies).

#2 Pokey The His Friends

After the first comic, the audience is already expecting a poorly drawn, error-ridden comic. Havelka bumps up the ineptness of the comic, by skipping over the entire adventure in three panels. In the first panel, Pokey and the Little Girl have found a canoe; we never learn how they encountered it, or what they are doing with it. They are suddenly thrust into danger, but before any action takes place, Pokey is safe and with his fellow penguins.

The deliberately unsatisfying storytelling is still pretty traditional irony, though. The interesting joke in comic #2 is Pokey’s misinterpretation of the threat. Rather than saying, “It is a good thing we escaped from the hole in the ozone layer,” Pokey claims to have escaped from the ozone layer itself. Thus, the comic sets up a theme of environmentalism, but annihilates the theme by misunderstanding the situation. The ozone layer itself becomes a personified enemy, and the comic’s environmental lesson is ruined.

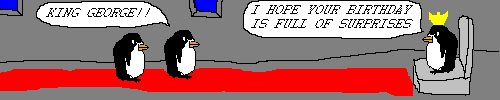

#5 The Abandoned Castle

Comic #5 is usually the first comic to strike the reader as brilliant. At the very least, it is usually the first comic to make him/her laugh out loud.

The first joke that people notice is that when Pokey suggests that he and his friend fly across the river, the next panel shows them in an airplane. Penguins are birds, and birds are associated with flying. However, penguins cannot fly. Pokey’ suggestion of flying is already somewhat ridiculous, but when he appears on an airplane, his idea makes sense. Nevertheless, because of the penguin-bird-flight connection, the audience does not expect him to use a plane. This joke plays around with the reader’s expectations concerning penguins and flight.

But a problem arises in the last panel: King George’s throne room looks exactly like the interior of the plane. Was that truly a plane? Is King George on the plane? If they were not on a plane, how did the penguins fly across the river? If they are still on the plane, why are there a throne room and king? Any way you interpret the succession of panels, it is partially sensible, and partly unexplained.

The kicker, and the most typically Pokey-esque joke in the comic, is King George’s comment. Pokey meets a random penguin, and the penguin later surprises Pokey with a birthday cake (inside either an airplane or the abandoned castle). In the climax of the tale, Pokey and his friend meet King George, a mysterious ruler who has not been introduced or explained (in fact, the castle was supposed to be abandoned). The penguins recognize King George, and his comment shows that he is aware of Pokey’s birthday. The stupidity of his comment is astounding. “I hope your birthday is full of surprises,” is an awkward, fortune-cookie-like phrase, which makes little sense after Pokey has already been surprised by a cake and a king in an abandoned castle (or airplane). King George’s surprise appearance seems to imply some amount of importance or profundity, but he only offers a ridiculous, almost meaningless birthday wish. It is not even clear that the phrase is a beneficent greeting. The placement of King George’s absurd phrase in the climactic/punchline position (the last panel) puts additional emphasis on the royal utterance. “I hope your birthday is full of surprises” almost fits; after all, it is Pokey’s birthday, and it has been full of surprises. But upon a moment’s reflection, the statement (and the king himself) is ludicrously out of place.

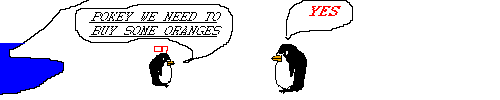

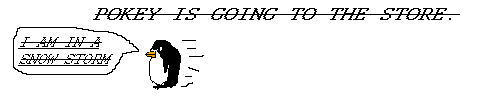

#39 The Price of Love

#39 is a short but deep comic, and yet another one that often evokes loud laughter. Pokey’s comment, “That is the price of love,” is the punchline of two jokes. First, Pokey has disappointed the Little Girl by bringing her the wrong kind of fruit; when he names that disappointment as the price of love, we understand what he means: in dealing with those we love, we must sometimes accept less than we desire. However, Pokey’s comment is ironic in light of the unimportance of the matter. Furthermore, it seems that Pokey’s improper fruit purchase was due to either deliberately ignoring the Little Girl’s request, or the confusion of the snowstorm. In either case, love has nothing to do with it.

The snowstorm is the second joke. Pokey encounters a snowstorm on the way to the store, and we unconsciously assume that this is the reason that his fruit purchase becomes muddled. However, this makes no sense. The storm occurred on the way to the store, so there was clearly no way that the storm interfered with the fruit. The storm could not have followed him into the store. And even if the storm had hit him on the way back, that doesn’t explain his fruit getting switched. The storm represents some random event that disrupts Pokey’s efforts, but the storm is an unsatisfactory disturbance. The storm is a thin pretense for Pokey’s incorrect purchase, which puts even greater emphasis on the outcome of the purchase; in other words, it puts greater emphasis on Pokey’s line, “That is the price of love.” The situation almost makes sense, but turns out to be an inept display of the “price of love.”

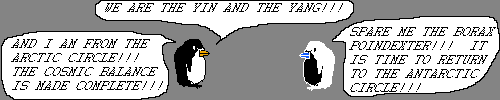

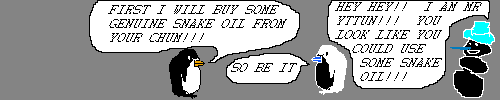

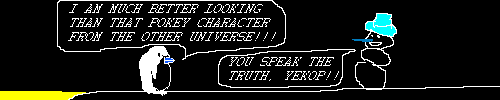

#80 Pokey and Yekop

This comic makes fun of children’s stories’ (animated cartoons and books) tendency to use irrelevant facts to introduce a fantastical journey. School children will read about dinosaurs, and suddenly a dinosaur will appear in the classroom; a kid will read about Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde, and will thereafter begin transforming into a monsterish alter ego. In #80, Pokey has a doctorate in theoretical physics, and is then transported to a nexus. The pseudo-profound pronouncements of Pokey and Yekop are laughable in themselves, but the real joke is that no explanation is offered for the transportation (or Pokey’s return); in cartoon physics, declaring that one has a degree in theoretical physics is sufficient to cause bizarre events. The terrible joke of the last panel mimics the final jokes of children’s cartoons and literature.

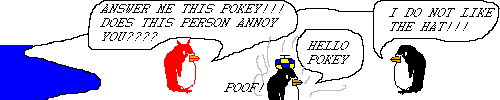

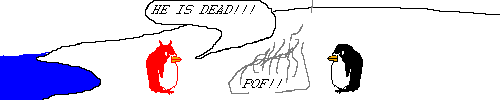

#100 The Devil

The logic of #100 is this: the Devil tricks Pokey into implicitly asking for a favor; the Devil grants Pokey the favor, and then claims his reward: Pokey’s wallet; the Devil then announces, like a motivational speaker, that he is “mastering the possibilities.”

This comic is a variation on the stereotypical human-and-the-Devil confrontation. The Devil appears and tricks Pokey into making a sinful request; however, Pokey’s “request” consists of admitting he doesn’t like someone. The Devil fulfills the implied request, and then takes his payment; however, instead of Pokey’s soul, the Devil takes his wallet. Finally, instead of a sinister and proud speech before departure, the supreme master of evil makes a silly statement of self-empowerment.

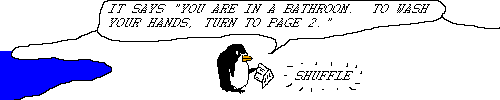

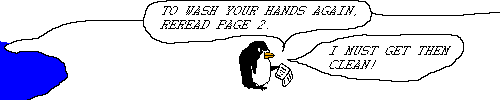

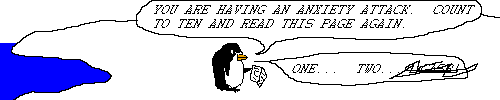

#159 The Hands Are Not Clean!!

#159 begins with a pretty standard joke style. An unusual premise, an obsessive-compulsive choose-your-own-adventure book, is introduced, and the comic possibilities are explored. When Pokey throws the book into the ocean, he is committing suicide in the fictional world of the book.

The second joke comes from an analysis of the first joke. If one could not move beyond the first few pages of the book, there would be no point in having more than a few pages. The Little Girl’s question, “What where on the other fifty pages?” reveals an inconsistency in the premise. Pokey’s reply, “Porn,” represents Havelka’s own thoughtlessness while establishing the premise. As Havelka created the obsessive-compulsive book without thinking the idea through, he supplies the ending pages with equal indifference.

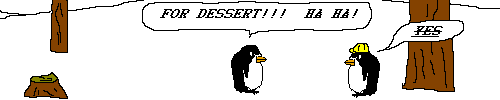

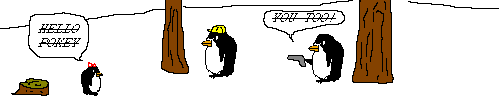

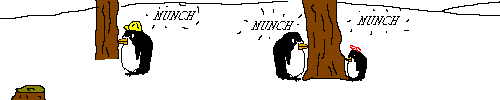

#165 Save The Trees

“Save the whales…for dessert!” is a sensible bumper-sticker, anti-environmental phrase. Havelka extends the phrase to another anti-environmental area in which it is ridiculous. After inventing the phrase, “Save the trees…for dessert!” Havelka applies it as a deliberate statement; Pokey and the lumberjack begin to eat trees, and force the Little Girl to join them at gunpoint. Pokey and the lumberjack are odd eco-terrorists, invented by a manipulation of a stupid anti-environmental slogan. The implied question is: would the above comic be any less ridiculous if it had involved whales rather than trees? The initial phrase is mocked by application in a new area.

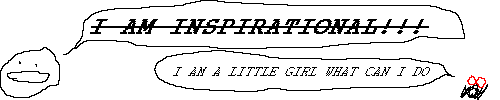

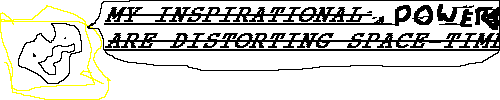

#229 Mary Lou Retton (Drawn by Mary Lou Retton)

This comic is a straightforward exaggeration of Mary Lou Retton’s laughable attempts to inspire children. The overblown exaggeration is a typical type of humor, which might catch the reader off-guard; Pokey succeeds in the realm of conventional humor, without its usual tactics. An additional joke is that Retton is named as the author, and the pictures become even worse than usual. When Retton ascends to the higher plane, Havelka’s artwork returns, implying that she actually has left.

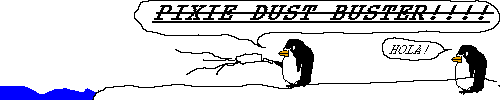

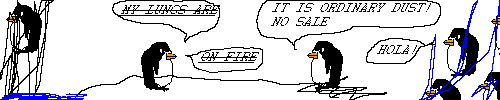

#238 Hola!

#238 is one of the many comics that inspire critics to condemn Pokey as random. Truly, I can not explain the “Hola!” portions of this comic. The initial joke involves a typical illogical-role-reversal; Pokey tries to force a customer to buy pixie dust, but upon discovering that the dust is ordinary, he refuses to sell. One would expect the customer to reject the dust upon discovering its common nature, but Pokey’s reaction implies that he is less willing to sell ordinary dust than pixie dust; in other words, pixie dust is worth less than regular dust.

My guess about the “hola” is that Havelka used the word without any deeper purpose, and then repeated it when another penguin began to enter. When he decided against the second entrance, he scratched it out, and didn’t know where to go with the comic. He wrote “hola” in the last panel because “hola” had become a running joke in the comic, but he didn’t know how to stretch out the pixie dust story any further. The last panel completes the third leg of the running gag, while admitting that the storyline had run dry.

In Conclusion

[Editor’s summary: Agosto vows to give a deeper analysis of each comic in the coming years. He asks readers to email any suggestions to him at ADA@subreality.org .]